EXCLUSIVE

EXCLUSIVECat Stevens, 77, Finally Tells All About Shocking Islam Conversion, Drug Trips, Fatwa Scandal — And How He Has Spent His Entire Life Dodging Death

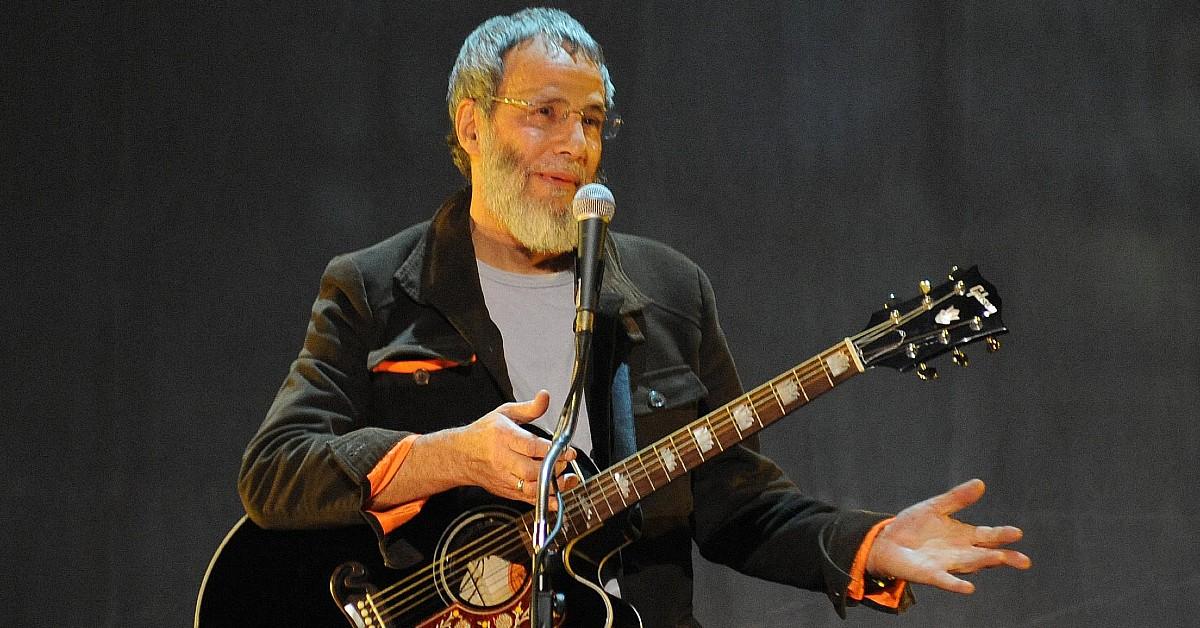

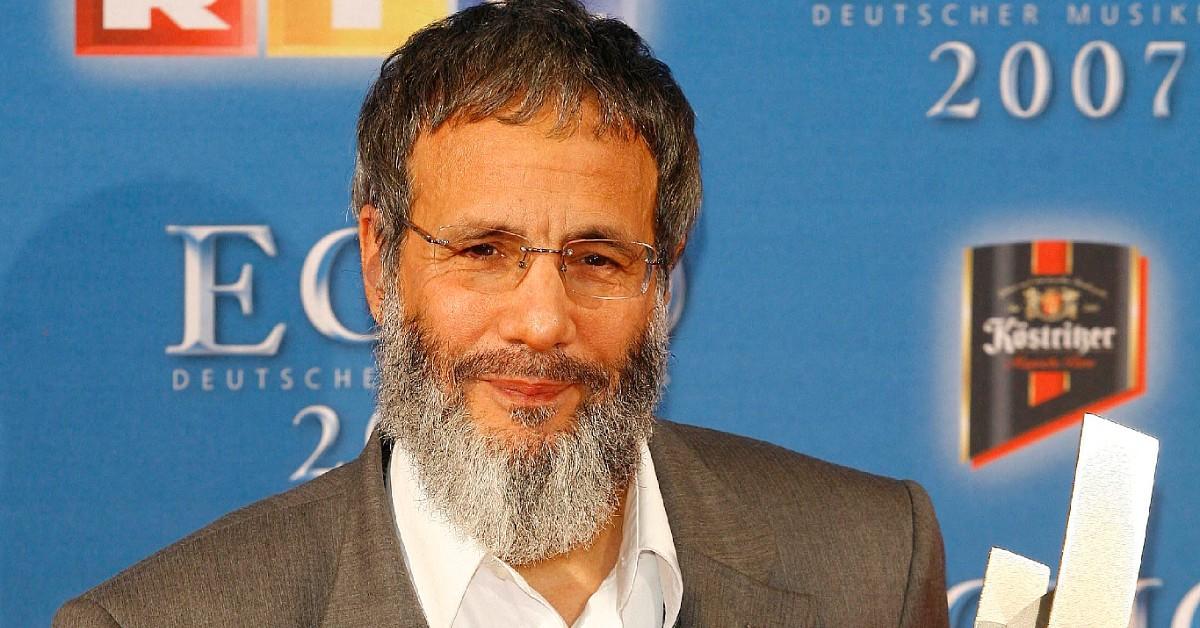

Cat Stevens dished about his shocking Islam conversation in his new memoir.

Nov. 27 2025, Published 7:00 p.m. ET

Cat Stevens has finally laid bare his near-misses with death – as well as his drug-fueled visions and dramatic conversion to Islam – in a sprawling autobiography that portrays a music icon who has been dodging disaster since childhood.

The singer–songwriter's new memoir Cat: On the Road to Findout – named after a track from his 1970 hit album Tea for the Tillerman – charts how Steven Demetre Georgiou, born "on the full moon of July 1948" above his parents' café in London's West End, morphed into Cat Stevens, global troubadour, and later Yusuf Islam, the devout musician who walked away from fame.

The new biography touches upon on how he repeatedly brushed against mortality.

Across its pages, it shows how he repeatedly brushed against mortality, from teenage recklessness and life-threatening illness to a Malibu undertow and a nightmarish LSD trip.

Death enters the story early.

As a teenager, living above the family café, Stevens almost plunged from the top of the Princes Theatre during a late-night roof-jumping dare with his best friend. Soon after his first burst of 1960s pop success faded, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis at 19 and sent to a West Sussex sanatorium for three months, a spell that ended his first career but, he writes, opened the door to the introspective songwriter who would give the world Wild World and Peace Train.

That second wave of fame brought new pressures. Touring turned corrosive and success fed a swelling ego.

The musician was diagnosed with tuberculosis at 19 years old.

Looking back on a strange package tour in Gothenburg, he says in the book: "Life on the road was becoming intolerable and so was I" – a line that captures both the grind and the self-absorption of his early stardom. The book also paints these years as a prelude to Stevens' total collapse – in emotional, spiritual and physical terms.

One of the most dramatic episodes comes off the coast of Malibu, where Stevens went swimming alone in treacherously cold water just as his career was cresting again. Dragged underwater and terrified, he bargained with a higher power that he would devote his life to God if he survived. Two years later, in 1977, he converted to Islam, took the name Yusuf Islam and began retreating from the music industry to focus on faith, family and charity.

The brush with death at sea is only one of several he has experienced throughout his life. Stevens is candid about a harrowing LSD experience in which, under the influence, he tried to stab himself with a coal shovel.

- 'Love Island USA' Star Nic Vansteenberghe Admits He's a 'Lucky Man' Amid Olandria Carthen Romance: 'We're Killing It'

- O-Town's Ashley Parker Angel 'Ready for a New Chapter' in Health and Wellness After Leaving Entertainment: 'More Exciting for Me'

- Mark Ballas Teases 'Crazy' Final 'Traitors' Episodes as Finale Looms

Want OK! each day? Sign up here!

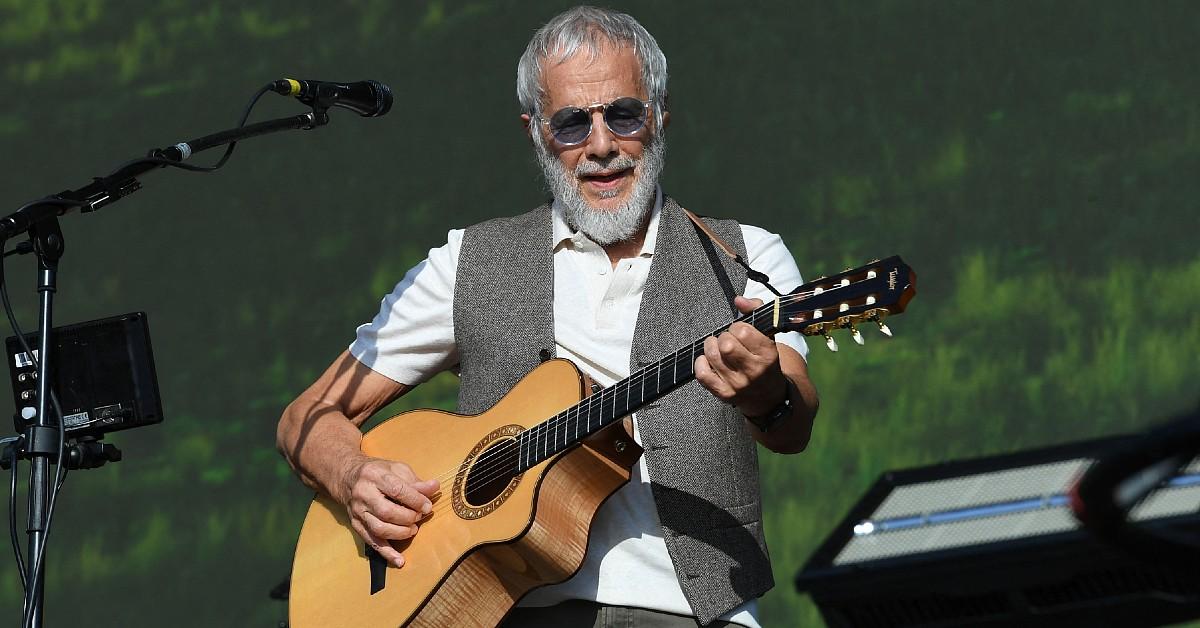

Cat Stevens' memoir was released in 2025.

The memoir links such episodes to a broader pattern of risk and restlessness, suggesting a man who repeatedly pushed his body and mind to their limits before pulling back.

Yet even as he embraces religion, Stevens does not erase the hedonism that came before. He sets his post-tuberculosis reinvention firmly within the post-hippie singer-songwriter boom, placing albums such as Mona Bone Jakon and Tea for the Tillerman alongside contemporaries while acknowledging how wildly success inflated his sense of destiny.

At one point he recalls playing record executives the new songs and said: "Behold: instant history!" – a boast the book presents with a hint of rueful humor.

Later chapters follow his withdrawal from mainstream pop into a quieter, if still controversial, existence centered on spiritual duty, education projects and family life. It also details his fatwa controversy.

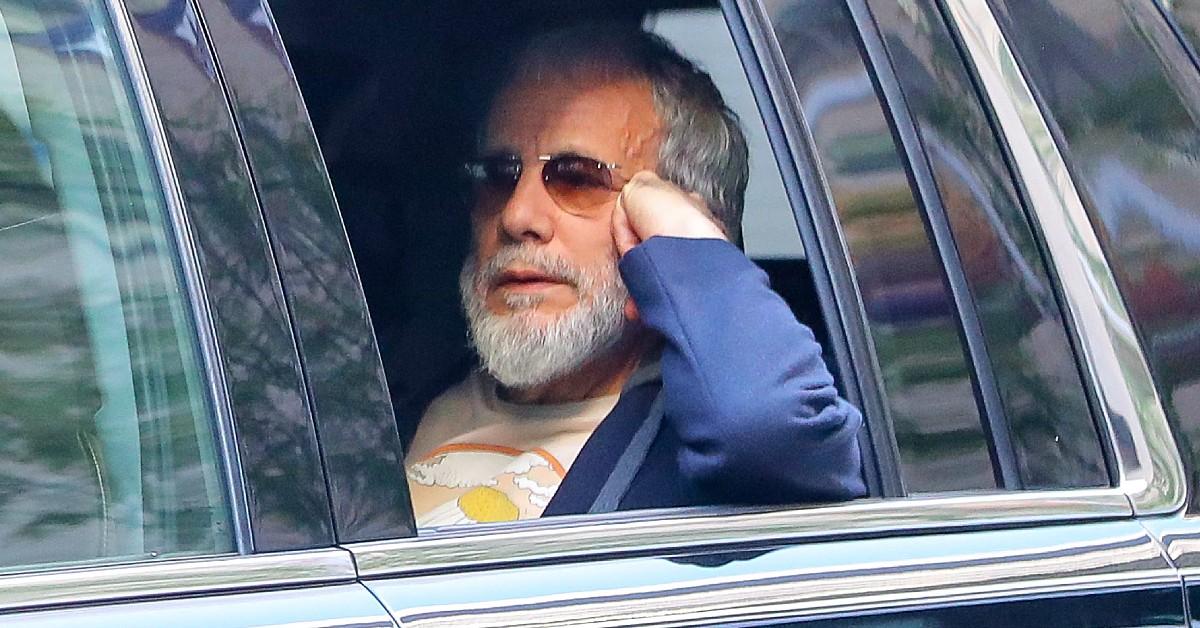

Cat Stevens converted to Islam.

His comments on the Ayatollah Khomeini's 1989 fatwa against Salman Rushdie were interpreted to mean he supported the death sentence.

But Stevens uses his book to insist he was merely outlining the Quranic position.

He also claims his words were unfairly edited on a TV discussion panel by people who didn't understand sarcasm. Throughout, the near-fatal moments act as hinges, turning the narrative from London rooftops to tuberculosis wards, from Malibu surf to psychedelic terror, and finally toward the faith that has guided Yusuf/Cat Stevens through the decades since.