NEWS

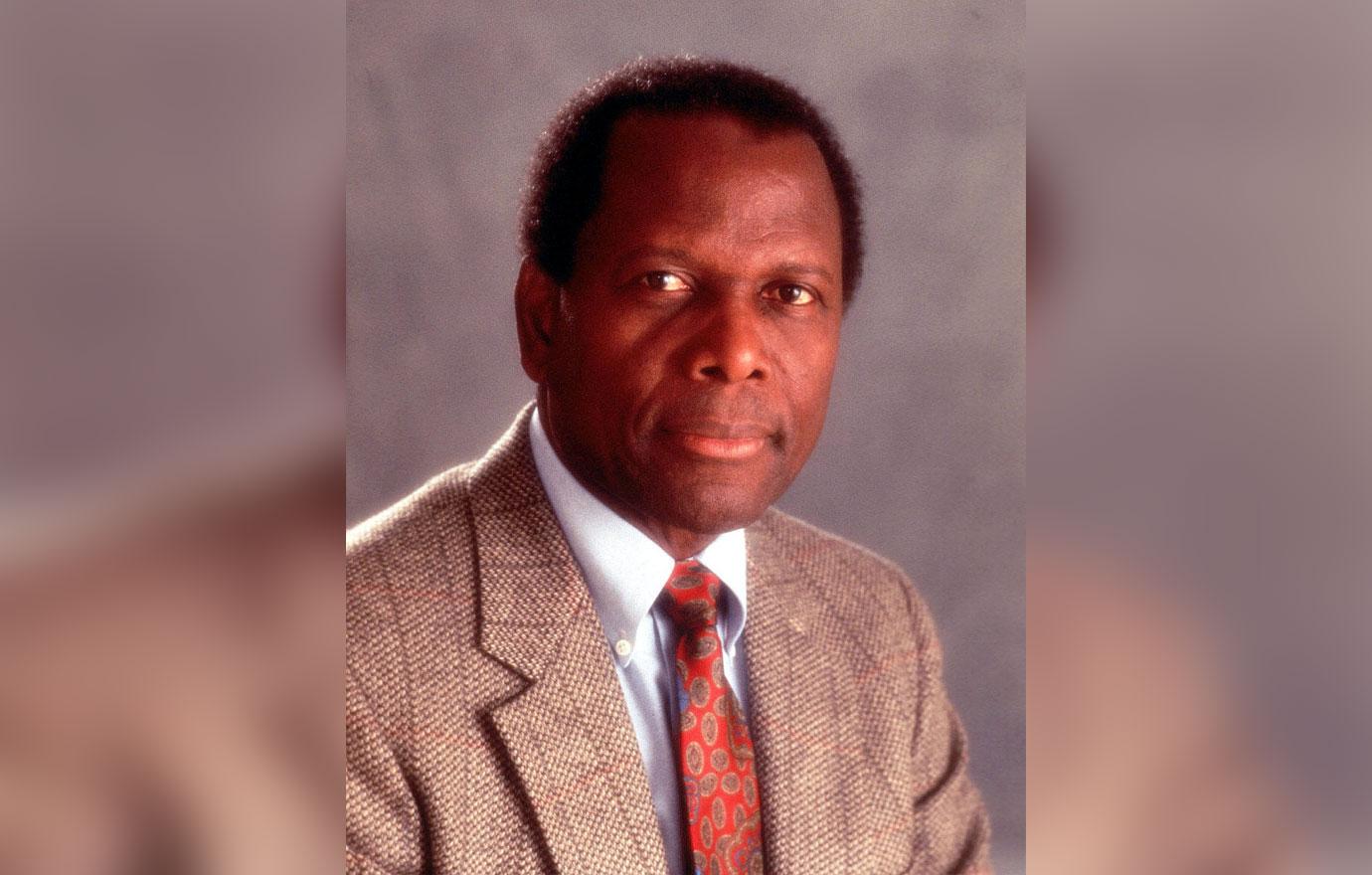

NEWSInside Sidney Poitier's Rise From Poverty To Superstardom With Unusual Twists & Turns

Jan. 7 2022, Published 5:07 p.m. ET

Sidney Poitier was born into poverty, but his rise to superstardom isn't the typical rags-to-riches saga.

His accent coincided with the civil rights movement, a time of remarkable transformation in America. That shift in the social fabric of the nation helped make Sidney's career possible and he, in turn, helped to inspire it.

But his story was nearly over before it began. Tomato farmer Reginald James Poitier and his wife, Evelyn, hailed from Cat Island in the Bahamas and were visiting Miami when Sidney arrived two months premature on February 20, 1927. Doctors said he wouldn't survive, but his mother refused to give up on their seventh child, and he surprised everyone by pulling through.

Back on the island, there was no electricity, no running water, no cars, or no schools, and all 10 Poitiers lived in a small thatched-roof hut. When Sidney was 11, the family relocated to Nassau, where conditions weren't much better, but his father was able to find work as a cab driver.

Sidney attended school for 18-months before dropping out to join a construction crew.

Tempted by an easier life, he soon embarked on a career of petty theft. Eventually Sidney's father became frustrated and sent him to Miami to live with his older brother Cyril. There, far removed from the island life he was accustomed to, he first saw the hidden underbelly of the American dream, prejudice and discrimination.

But he also saw the possibility of a life beyond his humble dreams. He began going to the movies frequently and wondered if he could pursue acting.

He also picked up some pointers from what he saw on screen. In his favorite genre, Westerns, "[I loved] to watch how the cowboys swaggered down the street," he said. To impress a girl, Sidney developed a cowboy-inspired swagger of his own. "I must have looked like an idiot," he confessed.

Living with Cyril for two years and working as a busboy, garbageman and a Fuller Brush salesman, Sidney became increasingly determined to succeed. After a brief move to Georgia at 16, with just a few dollars in his pocket, he boarded a bus to NYC.

Arriving, he was "stupefied by the noise," he said. "I had never seen so many [people] in my entire life."

He landed a dishwashing job and slept in a pay toilet at a bus terminal, which he jokingly dubbed, "The Executive Suite." Overwhelmed by the summer stench, he relocated to sleeping on the roof of the towering Brill Building wrapping himself in newspapers to stay warm.

In 1943, discouraged by his limited employment prospects and with winter approaching, Sidney lied about his age and joined the Army. He hoped to serve in a warmer climate. Instead he was assigned to the 1267th Medical Detachment, which was stationed at a mental hospital in chilly Northport, Long Island.

After a few months of witnessing patient abuse, Sidney wanted out. Rather than admit that he was underage, he decided to feign insanity. Turns out, he was a brilliant actor, even then: He was so convincing he was sent to a psychiatric ward for treatment. After weeks of counseling, he was discharged on December 11, 1944.

Back in Manhattan, working a variety of dead-end jobs to survive, Sidney saw an employment listing in a Harlem newspaper that would change his life. It read: “Actors Wanted by Little Theatre Group.”

Sidney responded knocking on the door of the American Negro Theatre. The visit did not go well. For one thing, he had never been on stage. Also, reading from a script he was handed, he spoke with a thick Bahamian accent. The theater’s co-founder threw Sidney out, telling him, “Stop wasting people’s time and go out and become a dishwasher or something.”

Most people would have given up. Not Sidney. Undeterred, he began an intensive self improvement regimen. He read constantly and studied the diction of radio performers. Six months later, he bravely returned for another audition, nervously reading a story aloud from True Confessions magazine.

Asked to improvise a wartime scene, he did an impression of James Cagney firing a machine gun before being shot dead. This time, Sidney was accepted.

He appeared in a variety of local stage productions, often with new found friend Harry Belafonte, who would land the lead in Days Of Our Youth, while Sidney became his understudy.

When Harry couldn’t make a special rehearsal arranged for the play’s original director, James Light, Sidney filled in. So impressed with the performance, Light asked Sidney to join the cast of his all-black staging of the Greek comedy Lysistrata.

Peering through the curtain at the large audience on opening night, Sidney was overcome with stage fright. Physically shoved onstage, he delivered his 12 lines of dialogue — in the wrong order! Amazingly, critics singled him out for his comedic performance. “Overnight, I was a hit!” Sidney said with a laugh.

But life was more than work for the young man. He was introduced by a friend to Ebony magazine cover girl and dancer Juanita Hardy. "[She] was the prettiest thing I had ever seen,” Sidney recalled.

Juanita was equally smitten, and they were soon going steady. They wed in Harlem in April 1950 and moved into a home in Astoria, Queens. Soon they welcomed three daughters, Beverly, Pamela and Sherri. (Another daughter, Gina, followed in 1961.)

Professionally, things were also looking up. In 1949, Sydney auditioned with director Joseph L. Mankiewicz for the film No Way Out. When he was offered the part of a doctor who treats a bigot, Sidney reluctantly admitted he had a prior commitment to a play. Mankiewicz told him to get out of it and Sidney did, earning strong reviews in his film debut.

In 1951, he appeared in the drama Cry, the Beloved Country, shot on location in South Africa. Because of that nation’s apartheid law, the only way Sidney could legally enter the country was to indenture himself to British producer Zoltan Korda. “It was a humiliation,” he reflected, “but sometimes you have to take a punch in order to land one.”

Despite receiving critical acclaim for his performance, Sidney was offered only routine roles over the next three years. “Hollywood, as a rule, doesn’t want to portray us as anything but butlers, chauffeurs, gardeners or maids,” a disappointed Sidney remarked in 1951. Between jobs, he invested in a Harlem restaurant specializing in barbecue and found some local acting gigs on live TV, most notably NBC’s anthology series Philco Television Playhouse.

Want OK! each day? Sign up here!

Sidney's breakthrough finally came in 1955 at age 28, when he played an inner-city juvenile delinquent in Blackboard Jungle. The film was a sensation, propelling Sidney to national prominence.

Suddenly, he was deluged with offers, including the role of an escaped prisoner in The Defiant Ones for producer/director Stanley Kramer. Released in 1958 to raves, the film earned Sidney an Oscar nomination for best actor — the first ever for a black actor.

Sidney was also asked to star in producer Samuel Goldwyn’s controversial film of the Gershwin musical Porgy and Bess. Believing that the script perpetuated racial stereotypes, the actor turned it down. Or so he thought. Without Sidney’s knowledge, his L.A. agent had told the powerful mogul that Sidney would star as Porgy.

Fearing a lawsuit and worried that Goldwyn could persuade other producers to blacklist him, the actor reluctantly gave in. In a chilly meeting with Goldwyn, Sidney told him, “I will do the part to the best of my ability — under the circumstances.” Despite his qualms, Sidney and a luminous Dorothy Dandridge lit up the screen as Porgy and Bess, and Sidney was proud of his work on the film.

The success of Porgy and Bess, however, brought with it personal turmoil for Sydney. It was on that movie’s set that he became smitten with co-star Diahann Carroll. “I invited her to dinner, telling her that, since we were both married, we would talk about our absent loved ones,” he later recalled. “And we did. I acted very, very gentlemanly for weeks, but halfway through the picture, we fell in love.”

After filming, Sidney told his wife, Juanita, what had happened. But the Poitiers decided to remain together for the sake of their daughters.

After starring in the award-winning play A Raisin in the Sun on Broadway, Sidney reprised the part in the 1961 film version. It cemented his reputation as both a fine dramatic actor and a charismatic movie star. Now officially an A-lister, Sidney made Paris Blues with Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. Diahann also co-starred. It was filmed on location in the romantic city of Paris, where Sidney became even closer to the beautiful actress.

Despite his professional success, Sidney felt upset and uneasy — and not just about his relationships. It was something bigger, and it forced him to see a psychotherapist. “It was a strange time for me,” he admitted. No matter how well he was doing, he realized that “I lived in a country where I couldn’t get a job, except for those put aside for people of my color.”

Deeply disturbed by the racism he saw all around him, he began to get involved in the civil rights movement. He joined Harry Belafonte and other stars in the historic March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. A year later, Harry convinced Sidney to help deliver $70,000 stuffed in a doctor’s black bag to civil rights activists in the South.

The two men were met by members of the Klu Klux Klan, who chased them in a car, attempting to run them off the road. Despite this harrowing encounter, Sidney continued to help finance the cause.

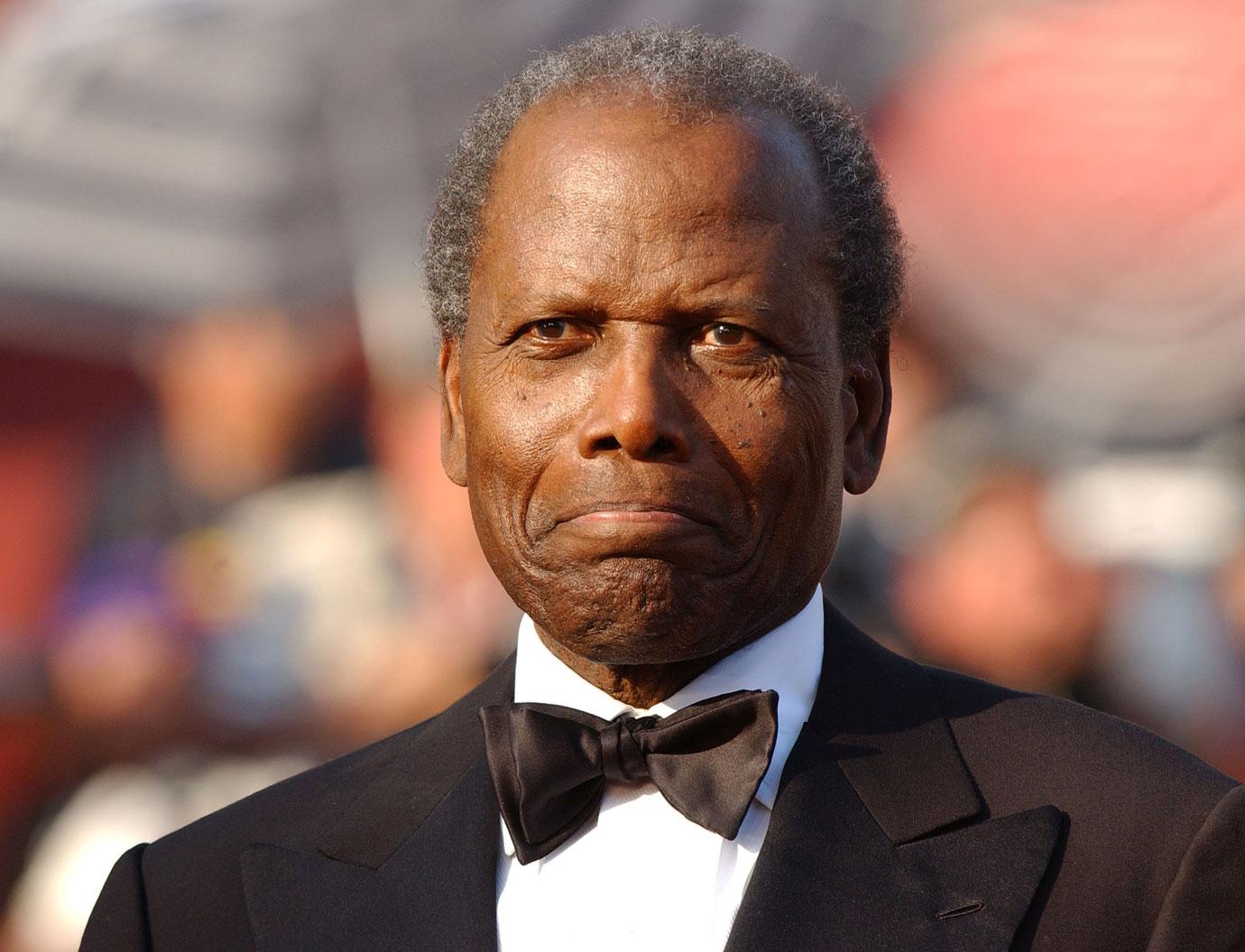

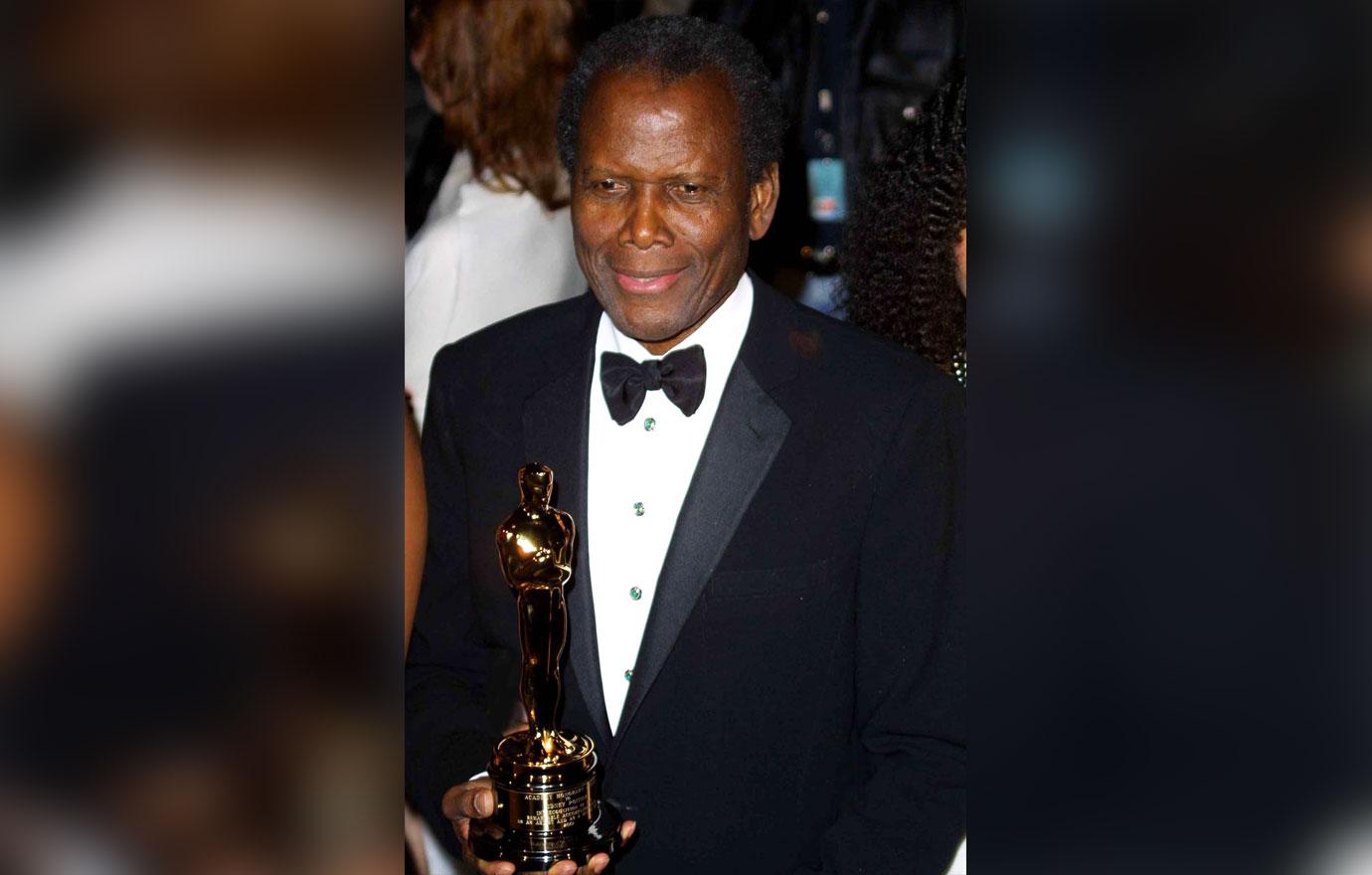

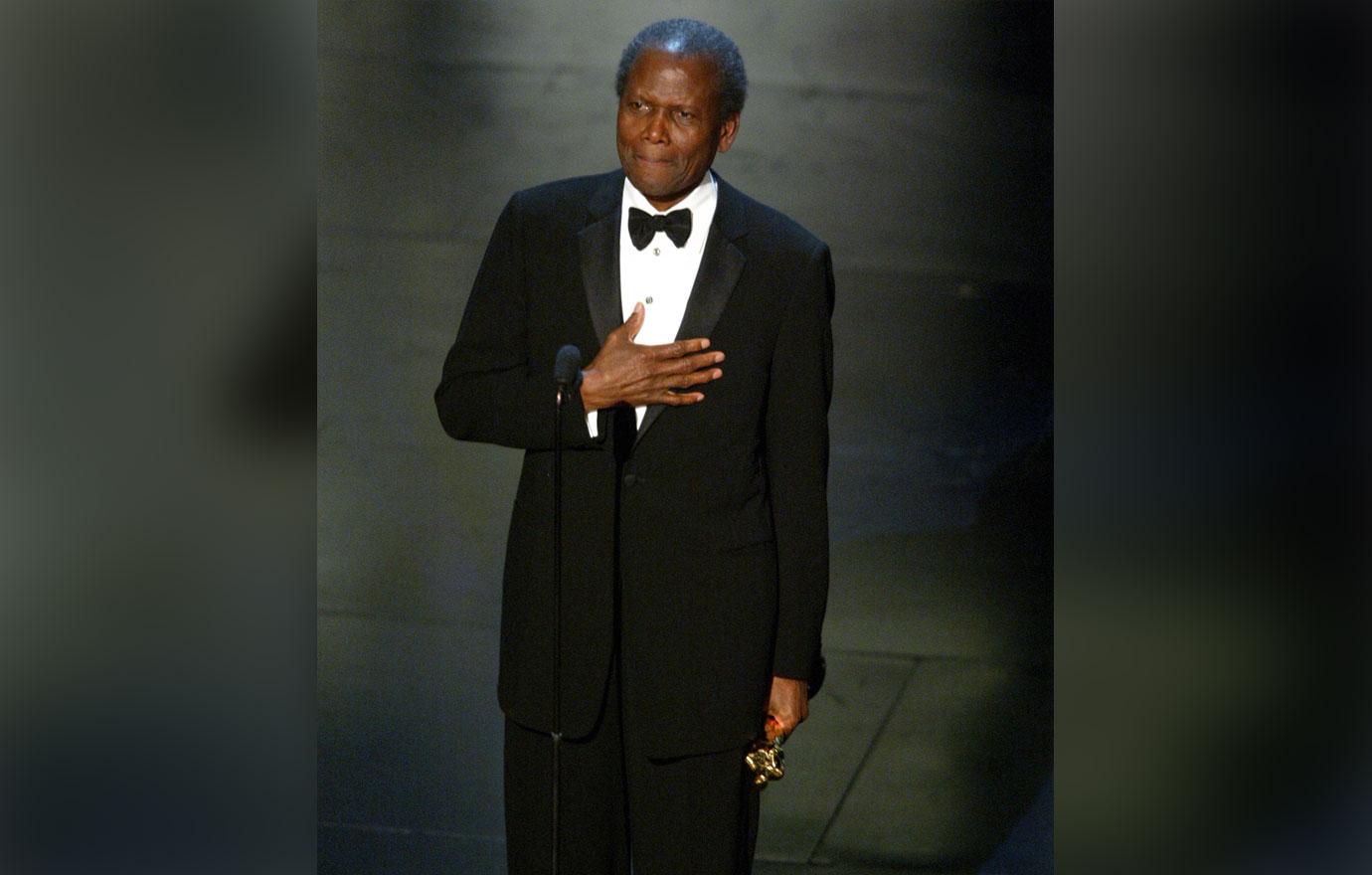

Then came the night that made history. Sidney became an inspiration to African-Americans everywhere when he won the 1964 Academy Award for best actor in Lilies of the Field. Sidney also shared a percentage of the film’s profits, confirming his status as a big, bankable and wealthy star.

Amazingly, Sidney’s career never seemed stumble. In 1967, he gave powerful performance in three unforgettable films. The first was as a teacher in To Sir, With Love.

The next was as homicide detectives Virgil Tibbs in In the Heat of the Night, where Sidney delighted audiences by taking no guff from his redneck co-worker, played by Rod Steiger. “Rod Steiger taught something invaluable,” Sidney said. “I had been pretending, indicating, giving the appearance of certain emotions but never, ever, really getting down to where real life and fine art mirror each other.”

His third film that year was Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, a landmark movie about race relations. Sidney portrayed a doctor engaged to a white woman (Katharine Houghton), whose parents were played by Hollywood royalty Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy.

“They were giants,” Sidney said. “It wasn’t easy for me to work opposite them. It was all so overwhelming. I couldn’t remember my lines. With the other actors I was fine… but when I got to play a scene with Tracey and Hepburn, I couldn’t remember a word.”

After blowing take after take, at one point Sidney filmed a scene in close-up, acting opposite two empty chairs! Audiences couldn’t tell, and the groundbreaking drama won cheers from critics and ordinary filmgoers alike.

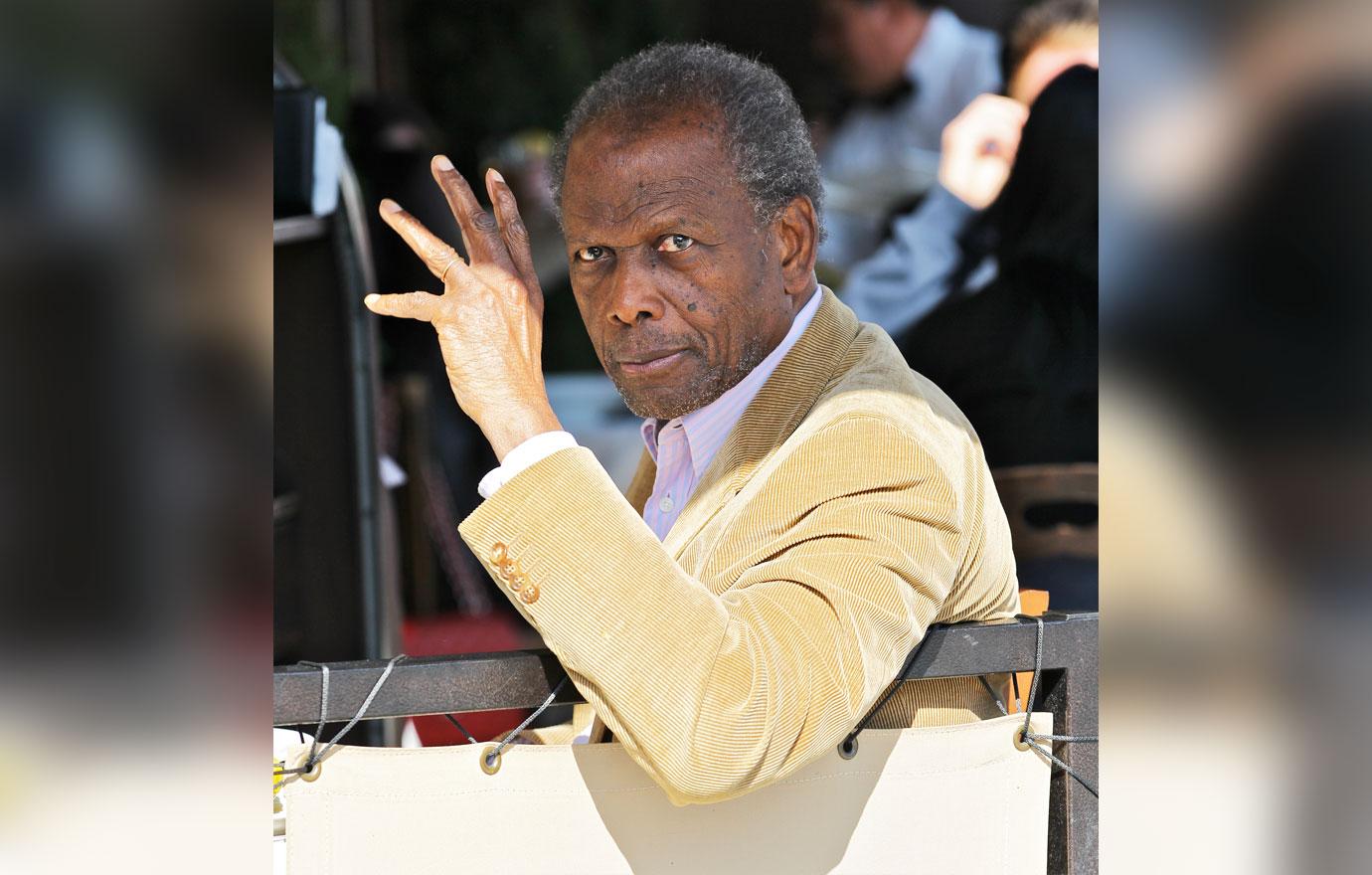

Sidney was the top box-office draw in America. And he decided it was time for a change. He knew he couldn’t remain this popular forever. “I used to sit and evaluate the decline and how I would try to engineer the rest of my career… that I level off with grace,” Sidney admitted. His solution was to try directing.

His first attempt, a play, Carry Me Back to Morningside Heights, close quickly. Discouraged, Sidney partnered with Barbra Streisand, Steve McQueen, Dustin Hoffman and Paul Newman to form First Artists Production Company in 1969, which was founded to select, finance, make and control every aspect of their films.

But the entire movie business was transforming. Fueled in party by Sidney’s breaking down of old taboos and barriers, movies devote to every facet of the African-American experience were suddenly being made for black and white audiences. Director Gordon Parks’ private detective film Shaft (1971) launched an explosion of films and black heroes, villains, singer and even monsters, like Blacula and Blackenstein!

These highly entertaining movies employed more African-American actors and crew members than ever before. “Suddenly, after too many years of little more than Sidney Poitier films, came a profusion of movies with black stars, male and female, macho guys and beautiful girls,” said Sidney. “It was terrific, and the response at the box office was tumultuous…. I went to see each and every one of them as they came out.”

Sidney’s own acting career was on the wane, though, partly because of the so-called “blaxploitation” films. Fortunately, he’d found love again with his co-star in The Lost Man (1969), Canadian beauty Joanna Shimkus.

They married in January 1976 and were blessed with two daughters, Anika and Sydney Tamiia. And after making a successful transition to film direction in 1972 with the western Buck and the Preacher (stepping in when the original director was fired), Sidney focused largely on working behind the camera, though he did continue to act.

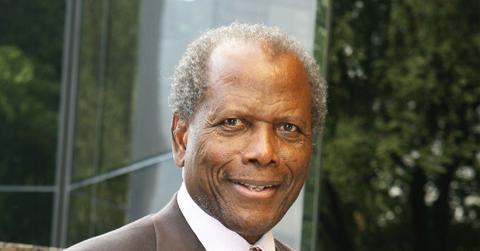

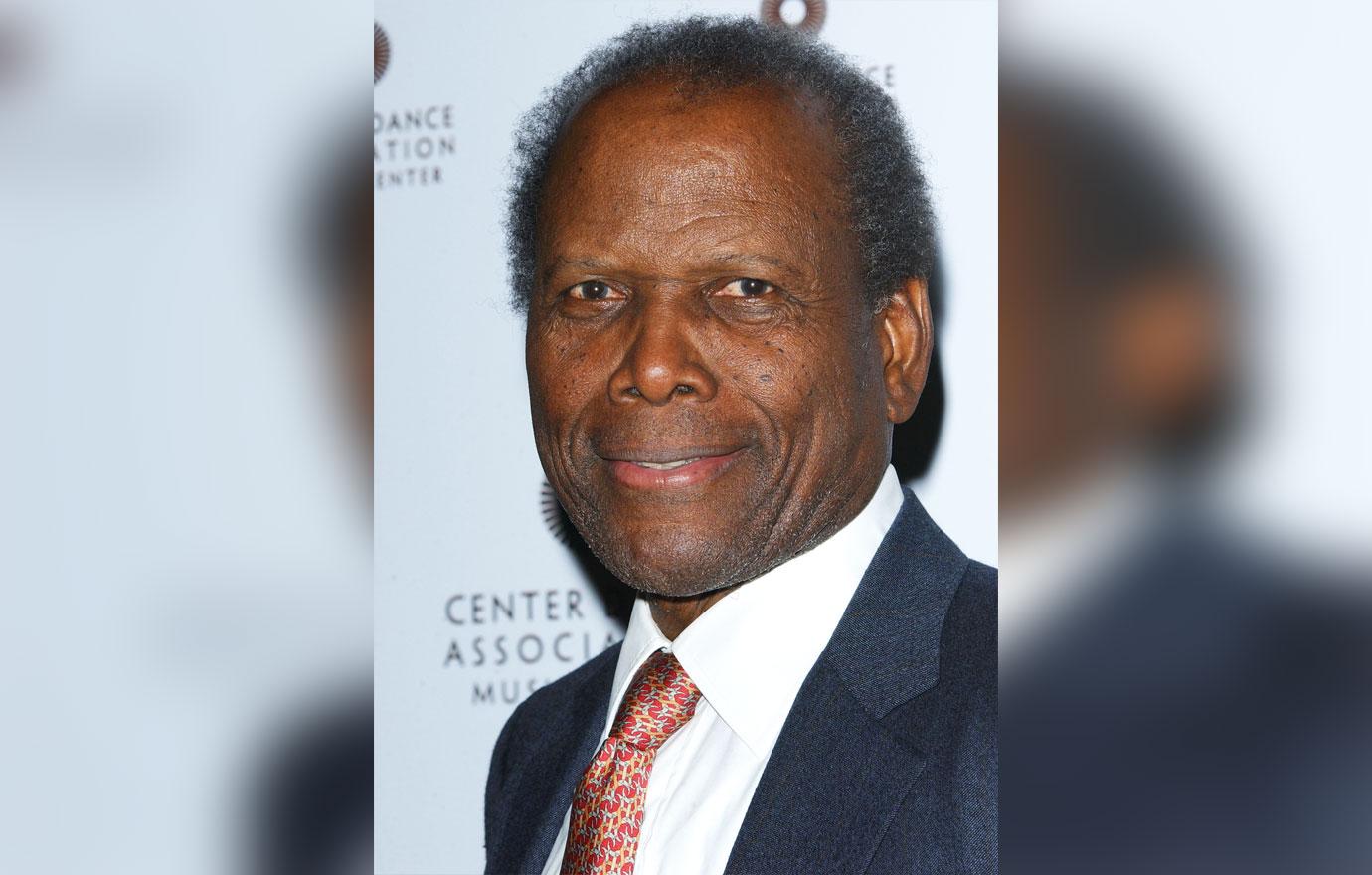

After an 11-year on-screen hiatus starting in 1977, Sidney returned with the 1988 films Shoot to Kill and Little Nikita, then co-starred with Robert Redford in the 1992 espionage thriller Sneakers. He was no longer a young leading man, but a respected elder statesman.

However, in 1993, after being treated for prostate cancer (the disease that had taken Cyril), Sidney slowed his career. His final film appearance was a 2001 TV movie, The Last Brickmaker in America.

He now devotes his time to humanitarian causes and to his family. “The world knows him as this iconic legendary figure,” says daughter Sydney. “But he’s also a really, really good dad.” At his 90th birthday celebration in February of 2017, wife Joanna called him “the most wonderful, generous, kind, honest man with the most integrity that I’ve ever known in my life.”

Sidney accepts these compliments with his characteristic humility and grace “I’m OK with myself, with history, my work, who I am and who I was,” the star recently reflected. “I wouldn’t change a single thing, because one change alters every moment that follows it.”